Mit »taktischem Urbanismus« wollen Aktivist*innen des Vereins Valyo das Budapester Donauufer inklusiver gestalten. ANITA GOCZA sprach mit CILI LOHÁSZ über Konzerte auf Brücken, Zusammenarbeit mit der Stadtpolitik und den ersten Sprung in die Donau seit 1973.

Der Text wurde in der Ausgabe 2/2023 von Info Europa veröffentlicht. Die vollständige Ausgabe ist hier zu lesen.

Ein Spaziergang entlang der Donau an der Pest-Seite gestaltet sich äußerst schwierig: Autos, Lärm, Asphalt und CO2 beherrschen die Orte mit der besten Aussicht auf Budapest. Der obere und untere Damm werden als Straßen genutzt. Diese sind nur schwer zu überqueren, auf einer kilometerlangen Strecke gibt es nur vier Zebrastreifen. Wer ans Ufer gelangen will, muss über Metallstangen klettern und selbst dann finden Fußgänger*innen keinen Gehweg, sondern nur einen schmalen Trampelpfad. Cili Lohász wollte das nicht mehr hinnehmen. Sie ist Mitgründerin der NGO Valyo – ein Akronym aus den ungarischen Wörtern város (Stadt) und folyó (Fluss) – und setzt sich für die Demokratisierung von öffentlichen Räumen entlang der städtischen Donau ein.

»Wir wollen den Fluss in das Wohnzimmer der Budapester Bevölkerung verwandeln«, sagt die Geografin. Die Idee zu städtischen Interventionen kam ihr nach einer Radtour entlang der Donau. »In Wien konnten sich die Teilnehmer*innen in der Donau abkühlen, in Budapest war das nicht möglich.« Sie merkte, dass sie zwar regelmäßig an der Donau Rad fährt, jedoch keine Verbindung zum Fluss selbst hatte: »Ich saß fast nie am Ufer.« Das wollte sie ändern.

Brücken besetzen, um Brücken zu bauen

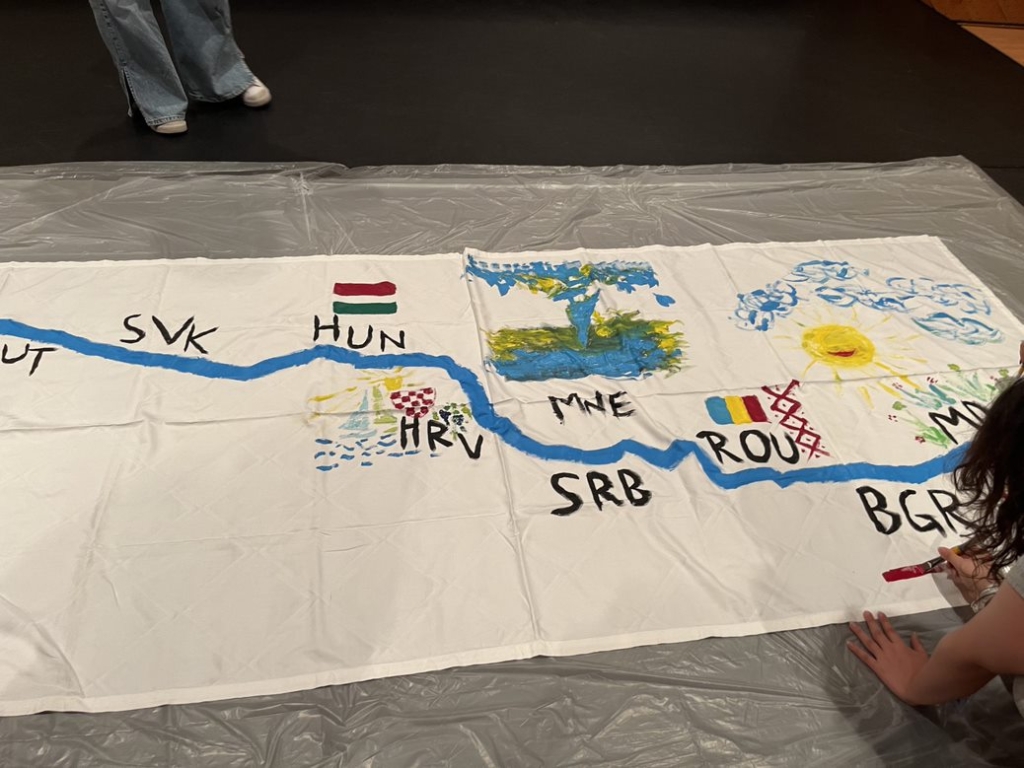

Neben Lohász gründeten ein Urbanist, ein IT-Spezialist und ein Soziologe Valyo im Jahr 2010. Sie alle hatten genug vom Kampf für ferne, globale Klimaziele und wollten etwas tun, das das Stadtleben tatsächlich verändert. 2011 kauften sie deswegen ein Zugticket nach Belgrad. »Es ist viel effektiver ein Foto mit Stränden am Fluss in Belgrad zu zeigen als in Wien«, erklärt Lohász. »Dann kann niemand einfach sagen: Die haben mehr Geld für die Umsetzung.« Die Valyo-Gründer*innen merkten, dass die Menschen in Belgrad eine intensive Verbindung zu ihren Flüssen, der Sava und Donau, hatten. Sie fanden Hausboote, Strände und Nachtclubs an den Ufern. Das brachte ihnen Inspiration für Budapest: »Wir mussten mit kleinen Aktionen starten. Hätten wir von Anfang an gesagt, dass Autos aus dem unteren Uferbereich verbannt werden sollen, wären wir für verrückt erklärt worden.«

Die erste Initiative war das sogenannte »Valyo-Ufer« an der Kettenbrücke in den Sommern 2012, 2013 und 2014 – ein Naherholungsgebiet mit bunten Bänken, Liegestühlen und Freizeitprogramm. »Es war relativ einfach zu organisieren«, sagt Lohász. »Wir holten die Genehmigung der Stadtverwaltung für die Nutzung des öffentlichen Raums ein. Unser Ziel war es, dass die Menschen diese Art der Ufernutzung später vermissen.« Die nächste Großaktion fand auf der Freiheitsbrücke statt. 2016 wurde wegen Bauarbeiten der Verkehr auf ihr für einen Monat gesperrt. »Schon nach ein paar Tagen belagerten Menschen die Brücke. Fußgänger*innen, Radfahrer*innen, manche machten sogar Yoga. Daran knüpften wir den darauffolgenden Sommer an.« Mit einer erfolgreichen Unterschriftenaktion ermöglichte Valyo eine autofreie Freiheitsbrücke an vier Wochenenden in 2017. »Alle Stadtbewohner*innen konnten mitgestalten«, erzählt Lohász. Die Events umfassten Tai-Chi-Kurse, Klassik- und Rockkonzerte, Malkurse, Theateraufführungen und Zirkusshows. »Die Menschen schufen einen demokratischen öffentlichen Raum, in dem alle sozialen Schichten und Altersgruppen vertreten waren.« Finanziert wurde dies über Crowdfunding. Laut Lohász zeigten die Aktionen, dass öffentliche Räume verschiedene Funktionen haben: »Man muss nicht immer zwischen Autobahn oder Spielplatz entscheiden. Derselbe Ort kann unter der Woche als Straße und an Wochenenden als Picknickplatz genutzt werden.« Gleichzeitig wollte Valyo die Kommerzialisierung der Plätze vermeiden: »Es sollte kein Konsumzwang herrschen, ein teures Foodtruckfestival kam für uns nicht in Frage.«

Politikum öffentlicher Raum

Ein großer Meilenstein in der Geschichte Valyos ist die Errichtung eines kostenlosen öffentlichen Strandes in Budapest in Zusammenarbeit mit der NGO Fák a Rómain (Bäume am Römischen Ufer). »Der Kieselstrand am Római-Ufer ist für mich auch eine symbolische Errungenschaft. Zu Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts galt die Donau als schmutziges und stinkendes Wasser, in das man nicht einmal seinen kleinen Zeh stecken sollte«, schildert Lohász. Tatsächlich war das Schwimmen in der Donau in Budapest seit 1973 verboten. Nachdem ein modernes Wasserreinigungssystem installiert wurde, und Testtage in 2019 und 2020 stattfanden, eröffnete die Stadt 2022 einen öffentlichen Strand mit Badeaufsicht. Das erste Mal seit fast 50 Jahren konnten die Budapester*innen wieder sicher in ihrem Stadtfluss schwimmen.

Der Strand ist beispielhaft für Valyos Zusammenarbeit mit dem Stadtrat. »Unsere Aufgabe ist es, das Potential bestimmter Veränderungen aufzuzeigen. Wenn sich unsere Versuche als erfolgreich erweisen, werden sie Teil der Stadtpolitik und wir können uns zurückziehen«, meint Lohász. Im Falle des Strandes bestünde ihre Rolle nur mehr darin, bedarfsweise mit ihrem Expert*innenwissen zu unterstützen. Und dieses ist breit gefächert. Unter den mittlerweile 30 Mitgliedern von Valyo finden sich verschiedenste Berufsfelder.

Lohász erkannte, dass es vor allem ab 2018 eine politische Wende mit Donau-Schwerpunkt gab. Der Fluss tauchte immer öfter in politischen Debatten auf und Bürgermeisterkandidat*innen begannen über die Donau und ihre enge Verbindung zur Stadt zu sprechen. Sie bemerkte auch den großen Erfolg des Projektes an der Freiheitsbrücke: Konkurrierende Parteien verwendeten Fotos der Brücke voller Menschen in ihren Kampagnen. Lohász wertet dies als Erfolg, denn Autofahrer*innen galten in Budapest stets als wichtige Zielgruppe für Politiker*innen. Mit dem Wechsel in der Stadtregierung von der nationalkonservativen Regierungspartei Fidesz zu einem Oppositionsbündnis wurde die Zusammenarbeit Lohász zufolge noch einfacher. Im Oktober 2022 unterzeichnete Valyo im Budapester Rathaus gemeinsam mit 17 weiteren Organisationen und Behörden eine Erklärung über die Zukunft des Ufers auf der Pest-Seite der Stadt. Unter den Unterzeichnern waren Organisationen, die sich aktiv für die alternative Gestaltung des unteren Damms aussprachen, und jene, die zuvor dagegen waren. Sie alle kamen zur Einigung, dass der Damm zugänglicher für Fußgänger*innen und Radfahrer*innen werden soll.

Probieren und Studieren

Stadtplanung ist ein sensibles Unterfangen, es müssen die Interessen verschiedenster Stakeholder*innen beachtet werden. »Bei der Gestaltung des Valyo-Ufers merkten wir, dass sogar Radfahrer*innen den Raum unterschiedlich nutzen, abhängig davon, ob sie Rennrad, Stadtrad, oder gemeinsam mit Kindern fahren«, resümiert Lohász. Valyos Ansatz nennt sich daher »taktischer Urbanismus«. Neue Ideen werden zuerst getestet, bevor man sie in großem Maßstab umsetzt. »So können wir sozialen Konsens erreichen.« Auch wenn ihr persönliches Ziel ein autofreies Ufer sei, weiß Lohász, dass sich dieses in weiter Ferne befindet. Phasenweise Autosperren würden aller dings Ideen liefern, wie diese Räume neu genutzt werden können. »Die Pandemie hat uns gezeigt, wie wichtig öffentliche Räume in einer überfüllten Stadt sind – Menschen sehnten sich danach, ihre Beine im Grünen zu vertreten. Dies hatte eine stärkere Wirkung als eine jahrelange Sensibilisierungskampagne.« Deswegen ist sich Lohász auch sicher: »Wenn wir wirklich wollen, finden wir für alle einen vernünftigen Kompromiss.«

Cili Lohász ist ausgebildete Biologie- und Chemielehrerin sowie Geografin. Sie arbeitete als Bildungsexpertin für Klimaanpassung und nachhaltige Energienutzung, bevor sie Valyo mitgründete.

Anita Gócza arbeitete 15 Jahre lang als Radio-Reporterin und Redakteurin für die nationale Radiostation in Ungarn. Seit 2011 ist sie als freie Journalistin mit Fokus auf kulturelle Themen sowie als Dozentin für Online- und Radiojournalismus an der Budapest Metropolitan University tätig.