Parliamentary Elections in Montenegro 2023

Read the briefing by Darija Benić, our former trainee, here:

The whole discussion is available on the YouTube channel of the IDM:

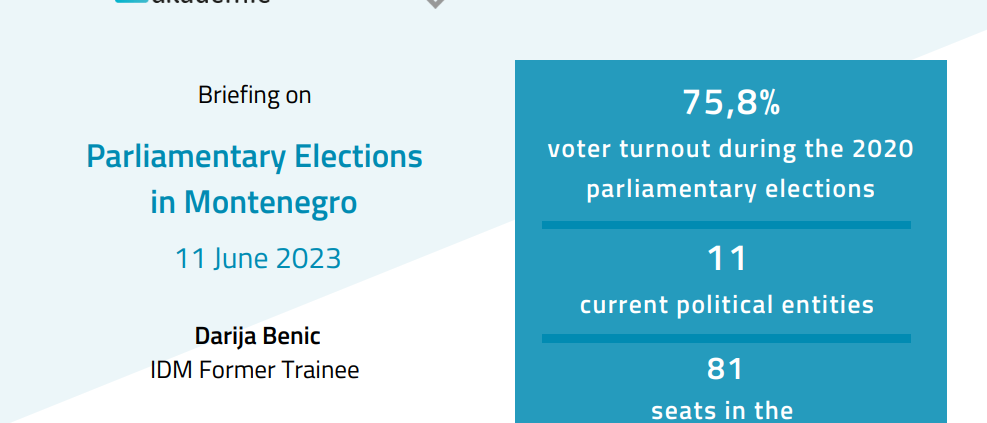

Early parliamentary elections, which will be held on June 11, are the twelfth parliamentary elections since the introduction of the multi-party system and the sixth in independent Montenegro. About 542,000 voters registered in the central voter register have the right to vote.

In the elections, 81 deputies are elected to the Assembly of Montenegro.

In the parliamentary elections, Montenegrin citizens will be able to choose between 15 electoral lists (parties and coalitions).

Experts view the considerable number of participants in the elections as a result of the Europe Now Movement’s increasing popularity, despite their varied political stances. Most of the other participants have prior involvement in Montenegrin politics.

Recently, the parties of the parliamentary majority dissolved the previous political alliances and established new ones, while the top officials and leaders of all opposition parties stepped down from their respective roles.

Montenegro has been undergoing significant political changes over the past few years. In 2020, the country’s ruling party, the Democratic Party of Socialists, lost its majority in parliament for the first time in decades. This marked a significant shift in Montenegrin politics and sparked hopes for a more diverse and competitive political landscape.

In essence, opposition to Đukanović’s leadership began when his party tried to seize the property of the Serbian Orthodox Church (the biggest denomination in the country, representing the entire Serbian minority and the vast majority of Montenegrin Christians). As a result, the Church organized religious processions, and the public expressed their disapproval.

Although Đukanović attempted to attribute blame to typical suspects such as Serbs and Russians for interfering in Montenegrin internal affairs, it was ultimately a coalition of a variety of groups, including Montenegrins, Serbs, Albanians, the Church, the civil sector, and many others, that caused his party to lose control of the government in 2020.

Following the defeat, the situation became more unsettled like most transitions. Three consecutive governments emerged after the party of Đukanović lost power. The first government was led by Zdravko Krivokapić, but they needed the support of Dritan Abazović, an ethnic Albanian. The government was later toppled by Former President Đukanović, and his party returned to power with Abazović serving as prime minister.

Soon after, Dritan Abazović made a groundbreaking deal with the Serbian Orthodox Church that reversed the attempts to take away Church property. This effectively resolved the issue that had caused dramatic division in Montenegrin society.

As a result, Đukanović forced the collapse of the second post-2020 government. Currently, the government couldn’t be formed, because Đukanović has refused to give Abazovic and some Serbian parties a mandate since mid-2022.

Then, Montenegro has had a “technical government” while a constitutional crisis emerged in the background. Namely, the formation of the Constitutional Court of Montenegro and other important institutions could not be formed.

The reason for this is partially because certain officials in those establishments were detained for their involvement in corruption and organized crime, as well as because several figures in Montenegro’s political environment are opposing any kind of action.

Regardless, Đukanović’s party has sustained its losing trend in numerous local elections that followed, with the most significant when they lost elections in the capital and most populated city, Podgorica.

In those elections, a new political option has been introduced, the recently created movement “Europe, Now!” is led by the youthful Milojko Spajić and equally young president-elect Jakov Milatović. In fact, Milojko Spajić has been a more prominent leader, but he was ineligible to run for the presidency because he has both Montenegrin and Serbian citizenship, a technicality which prevented him from running for the highest office.

Thus, a previously lesser-known politician with little experience in politics became the front-runner and defeated the 32-year-long reign of Milo Đukanović.

He was supported by the entirety of the Serbian minority, a significant part of the Montenegrin majority, the entirety of the civil society, all civic platform parties, the Serbian Church, an ethnically Albanian Prime Minister and– both pro-Russian and pro-European parties in Montenegro.

The true implications of these elections are affecting more internal affairs rather than its foreign policy or strategic position; All parties participating in both the recent presidential and 2020 elections have expressed support for Montenegro’s accession to the EU.

Nevertheless, Montenegro is still experiencing political turbulence due to numerous internal divisions. While these elections were necessary for national reconciliation between Montenegro’s two largest ethnic groups, it is uncertain how long the winning coalition will stay united after the defeat of Milo Đukanović.

The complicated political situation in Montenegro is likely to persist, and the restructuring of institutions and political systems will need to be more robust than in other areas of the Balkans.

The upcoming elections will be crucial for the future of Montenegro, as they will determine the country’s political direction and leadership.

The country’s accession to the European Union will likely be a key issue, with some parties advocating for closer ties with the EU and others pushing for a more isolationist approach.