Sebastian Schäffer

Milan Radin: Der Tormann, Leykam (2021)

For this summer, I recommend a lighter reading, which combines two of my favourite things: The Danube Region and football. The story follows Helmut Duckadam, a Romanian goalkeeper, who saved four penalties in the European Cup Final 1986 against FC Barcelona, ensuring the victory of Steaua București. It taught me a lot about Banat Swabians, Arad County, Romanian football and the country in general. Erhard Busek gave me the book and it had sat on my shelf for far too long. I’m glad I finally read it. The mixed narrative style of Milan Radin might be an acquired taste, however, for me it made it easier to put down and pick up again. Despite knowing how the career of Duckadam would develop, I felt myself rooting for him while reading, which made it quite engaging for me.

Daniela Apaydin

Summer in Odessa; Irina Kilimnik (2023)

When bombs fall, dreams collapse along with buildings. Before the war, that meant feather-light summer evenings by the sea in Odessa, love-filled glances between friends, family conflicts, and everyday problems. “Summer in Odessa” tells the story of a city where all of this was possible because the war had not yet torn craters through the cities and hearts of the country and its people. In the summer of 2014, it was evident that the country was in turmoil. However, Olga, a medical student, commutes without much interest in politics, somewhat aimlessly navigating between her family’s expectations, her imposed studies, and a few complicated relationships. Gradually, the personal and political developments in Olga’s life intersect, leading her to make a momentous decision. Irina Kilimnik’s fluidly narrated family saga is an endearing love letter to a city where, hopefully, dreaming will once again be pleasant.

Sophia Beiter

Picnic on Ice (original Russian title “Smert’ postronnego”); Andrej Kurkow

“Picnic on Ice” tells the story of Viktor, a loner who writes obituaries for the living and gets entangled in the workings of the Ukrainian mafia. His roommate is a depressed penguin who lives in the bathtub. Unpretentiously, satirically, and melancholically, Andrej Kurkow takes us into the world of a failed writer in post-communist Kyiv of the nineties.

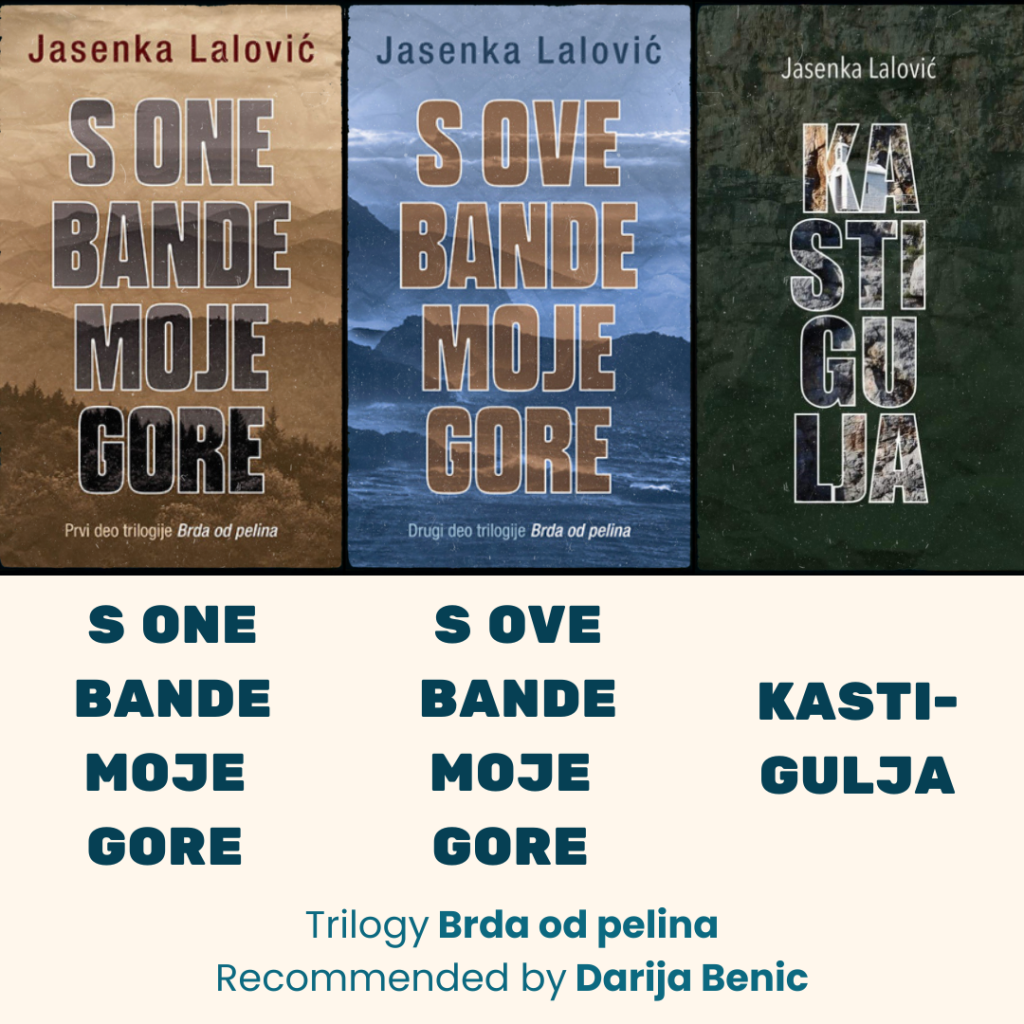

Darija Benic

Trilogy “Brda od pelina” (“Wormwood hills”), which consists of the books: “S one bande moje gore” (“On the other side of my mountain”), “S ove bande moje gore” (On this side of my mountain”) and “Kastigulja”; Jasenka Lalović (only in Montenegrin)

The trilogy “Brda od pelina” is an emotional story about the role of women in Montenegrin society – a kind of tribute to women who stoically bore the burden of the times they lived in, and who were unfairly pushed aside. From book to book, the story shows how their destinies come together with all the customary, linguistic and cultural diversity in the period from the end of the 19th century to the capitulation of Italy in the Second World War.

Info

Did you know that Readers of Europe 2023 at the EU Library this year is focusing on books by female authors? The permanent representations are recommending the best women writers from their countries. Learn more here.

Kinga Brudzińska

Maciej Popowski , 2015)

Despite its title and format suggesting otherwise, this book is not a comprehensive guide to the European Union. Rather, it takes on a half-joking, half-serious approach, offering a subjective and literary portrayal of the Brussels microcosm in its various aspects: local and international, historical and political, moral and cultural. Through its pages, one gains insights into the workings of the European Union, office life, prominent figures in the Brussels theatre, and most importantly, the experience of s living in Brussels.

Lucas Décorne

The Globalization Myth: Why Regions Matter; Shannon K. O’Neil (2022)

For this summer, dive into this book, which opens a fresh perspective on globalisation, revealing that the real story of the global economy over the past four decades is not just about traditional notions of globalisation. Instead, the book explores the significance of regionalisation and its potential implications for economic competitiveness and prosperity, offering valuable insights for anyone interested in understanding the dynamics of the modern global marketplace.

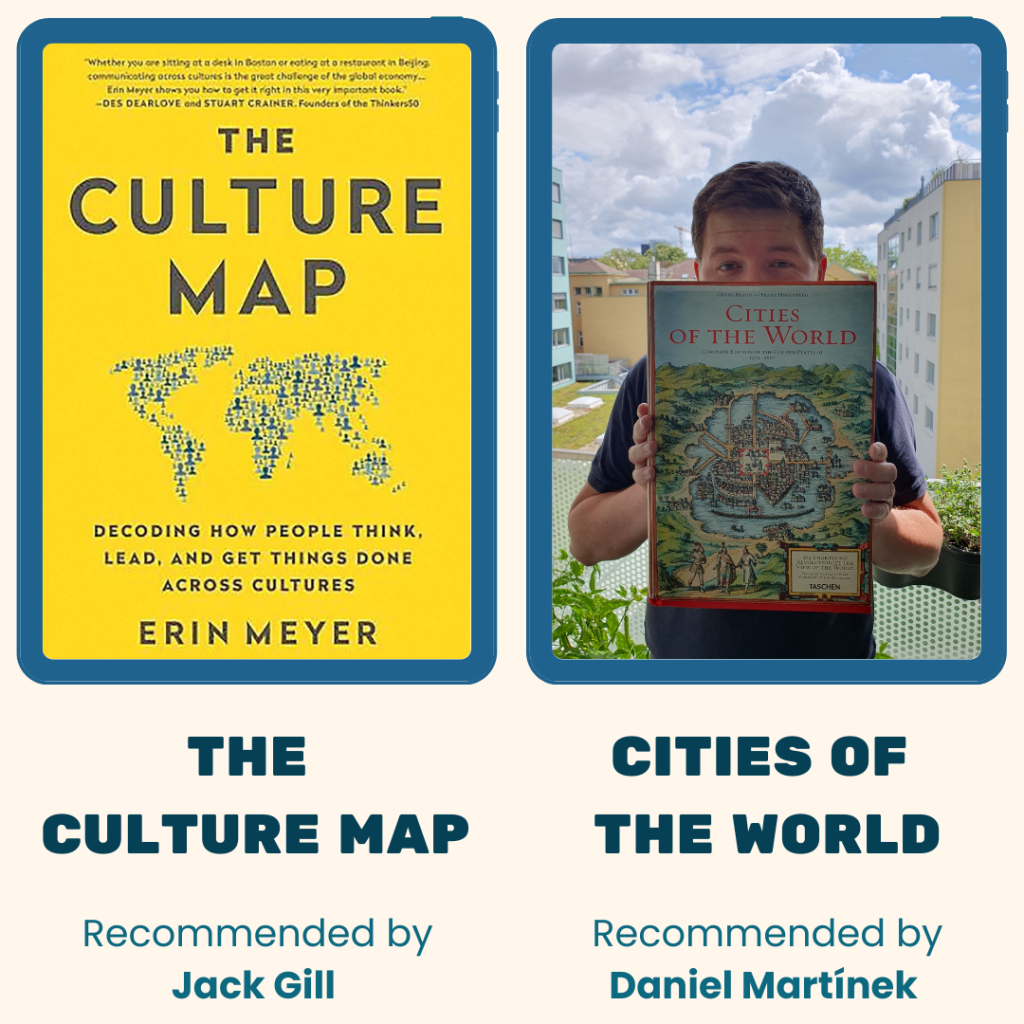

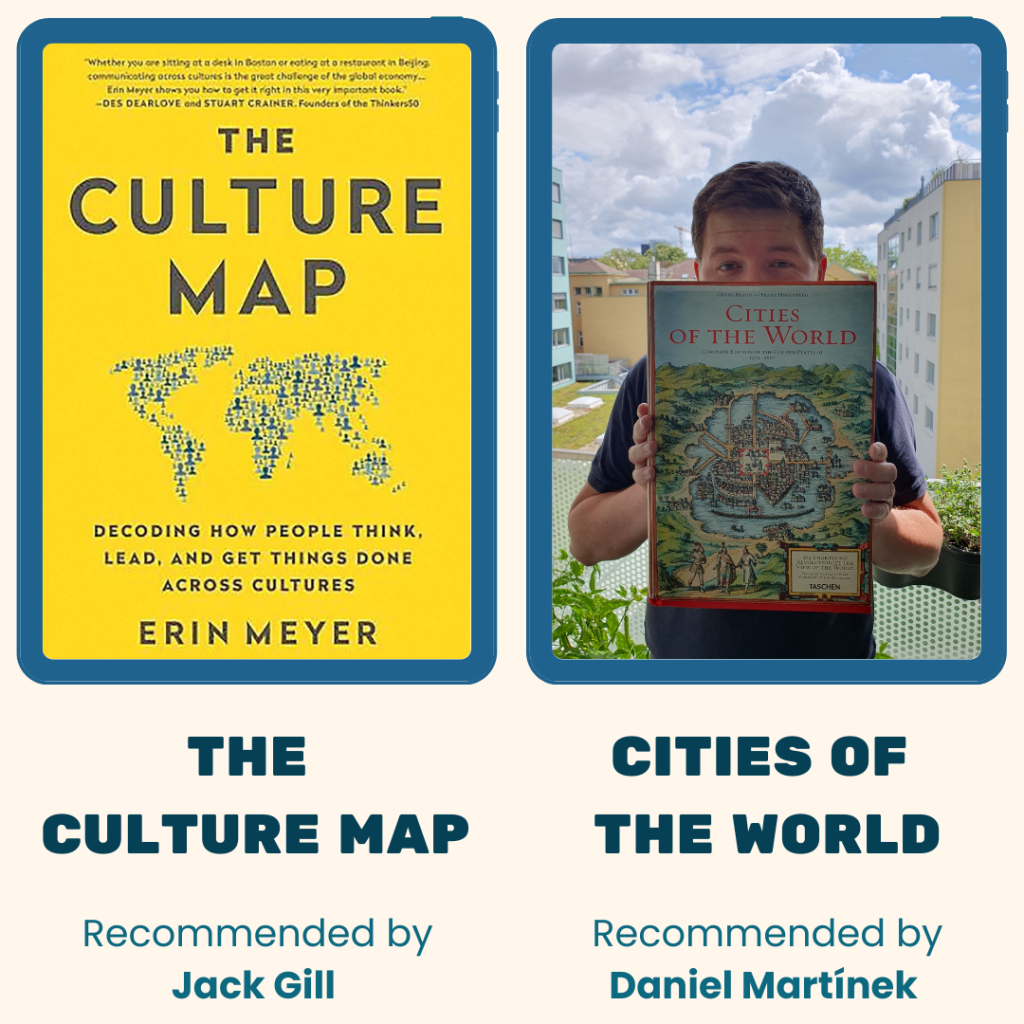

Jack Gill

The Culture Map; Erin Meyer (2014)

In areas of great cultural and linguistic diversity, like the Danube Region, cross-border exchange and cooperation between peoples can often be challenging. Moreover, even learning about other cultures can leave you ill-prepared for encounters with people from other countries. I chose this book because the author, Erin Meyer, offers ways to measure the “distance” between cultures using a number of metrics that measure specific traits common to all cultures. For instance, in some cultures, decisions are reached through consensus in flatter hierarchies, where the boss is just another team player, while in other cultures strict hierarchies ensure top-down decision-making and that people know their place in relation to their superiors and subordinates. To learn where your own culture sits in relation to others, and how to engage with people from other cultures, I recommend this book.

Daniel Martínek

Cities of the World; Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg (1572-1617)

For many, summer is a symbol of travelling and discovering new places. This collection of more than 350 historical engravings of important cities around the world is sure to inspire you as you plan your next adventures. Looking at this or that plan of a city from the time of the Renaissance makes you want to visit places across Europe, many of them also in the Danube Region. As a trained historian, I was particularly pleased when I was gifted the book last Christmas.

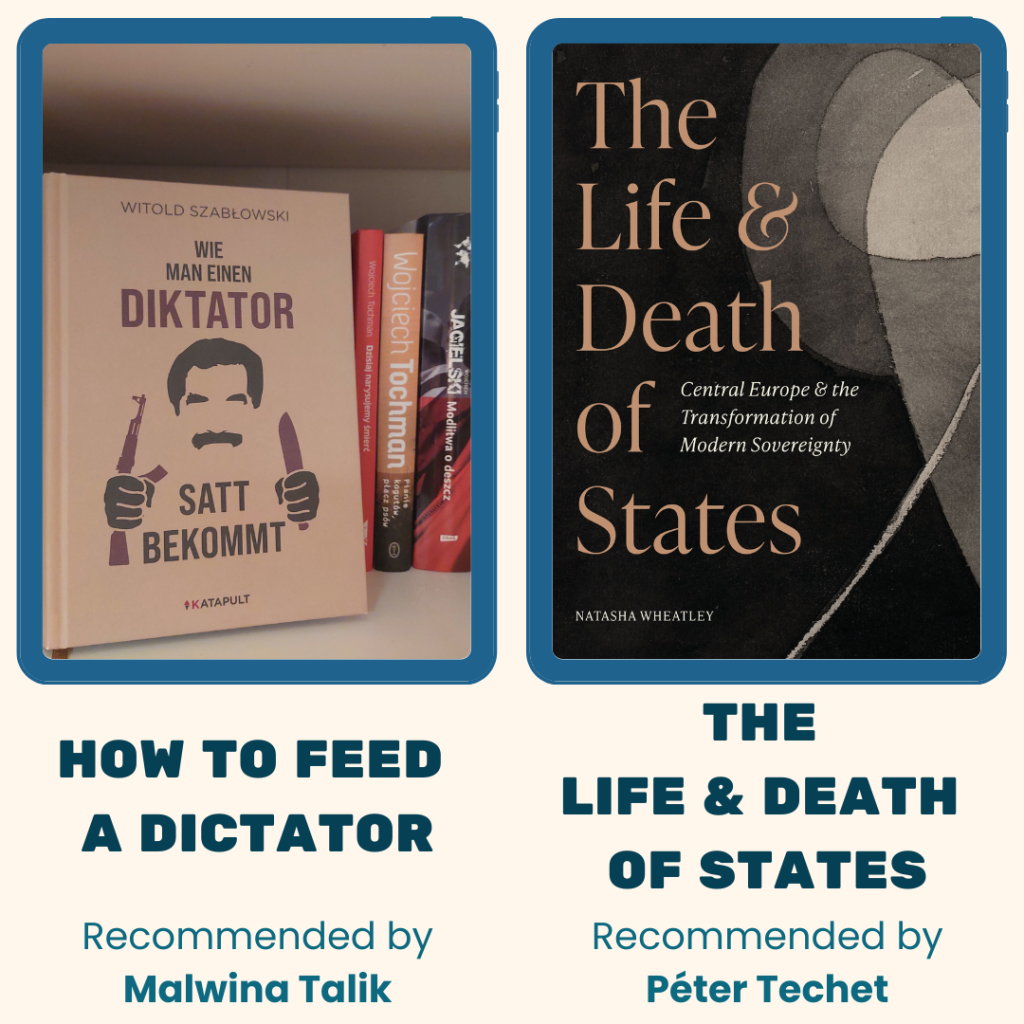

Malwina Talik

How to Feed a Dictator; Witold łowski (2019)

Reportage is to Poland what crime stories are to Scandinavia. Polish non-fiction writing has gained international recognition thanks to authors like Ryszard Kapuscinski, who paved the way for others to follow, such as Justyna Kopinska, Wojciech Jagielski, Wojciech Tochman, and the author of the book I recommend this summer – Witold Szabłowski.

“How to Feed a Dictator” was presented to the IDM by the Polish Institute during one of the IDM Melanges. I selected this book because, through its witty style and personal stories of chefs, it provides a sobering reminder of how authoritarians and dictators can gain and maintain power for decades in any place around the world when the circumstances are conducive. The book offers insights into how people may succumb to the charm of dictators, even when they are aware of their crimes (“but he always took care of his family,” “he was generous/modest,” “he had such a difficult life,” “others were even worse”), or adapt to survive in unpredictable and often cruel environments.

This is an excellent summer read as it is engaging and easy to follow, while also delving into profound questions about how societies and political systems operate (you may even discover some interesting recipes, though dining like a dictator might not be your preference).

The book is available in Polish, English and German.

Péter Techet

The Life and Death of States. Central Europe and the Transformation of Modern Sovereignty; Natasha Wheatley (2023)

Habsburg Central Europe is considered a “laboratory” for historical research, as Habsburg Studies must develop new concepts to describe the multiethnic, multireligious, and legal complexity of the former Danube Monarchy. Transnationality, national indifference, multiple identities, cross-border cultures – Habsburg Studies offers fresh perspectives to historians from diverse regions and time periods. In her new book, the Australian (not Austrian!) historian Natasha Wheatley delves into the legal ideas that emerged in the Habsburg Monarchy, foreshadowing postmodern, post-national approaches. The title of Wheatley’s book not only describes the disappearance of old states and the emergence of new ones after 1918 but also traces how Central European legal ideas envisioned transnational concepts beyond statehood during the interwar period. For those seeking to understand present-day debates on the European Union or transnational cooperation from a “longue durée” perspective, especially in the context of (post-)Habsburg Central Europe, this book is a fascinating read. Moreover, it is written in a manner that is understandable even for non-historians and non-lawyers.