Gemeinsam mit seinen Kollegen aus Warschau, Prag und Budapest gründete Bratislavas Bürgermeister Matúš Vallo 2019 den Pakt der Freien Städte – mit dem Ziel, sich anti-demokratischen Tendenzen in der Region entgegenzustellen. Der Ukraine-Krieg zeige, wie falsch Viktor Orbáns illiberale Politik sei, so Vallo im IDM-Interview. DANIELA APAYDIN hat mit ihm über die Veränderungskraft von Städten und ihren Allianzen gesprochen.

Mit einiger Verspätung schaltet sich Matúš Vallo zu unserem Zoom-Call hinzu. Er wirkt geschäftig, entschuldigt sich für die Wartezeit. Interviewanfragen von österreichischen Medien seien eher selten, an internationaler Aufmerksamkeit mangele es aber nicht, heißt es aus dem Pressebüro. Vallo spricht fließend Englisch. Er hat in Rom Architektur studiert, in London gearbeitet und erhielt ein Fulbright-Stipendium an der Columbia University in New York. Als politischer Quereinsteiger wurde er 2018 zum Bürgermeister von Bratislava gewählt. Im Herbst kämpft der 44-Jährige um die Wiederwahl zum Bürgermeister.

Herr Vallo, der US-amerikanische Politikberater Benjamin Barber argumentiert in seinem Buch »If Mayors Ruled the World« (2013), dass BürgermeisterInnen wirksamer auf transnationale Probleme reagieren als nationale Regierungen. Manche sprechen in diesem Zusammenhang von einer »lokalen Wende« des Regierens und Verwaltens. Leisten Städte und BürgermeisterInnen wirklich bessere Arbeit?

Ich kenne das Buch, und ich glaube an dieses Narrativ. Wir haben in den letzten Jahren erlebt, wie Regierungen den Kontakt zu ihrer Basis verloren haben. Als Bürgermeister kann ich diesen Kontakt nicht verlieren, selbst wenn ich das wollte. Alle guten BürgermeisterInnen, die ich kenne, gehen gern durch ihre Stadt und treffen Menschen. Manchmal halten sie dich an und erzählen dir von einem Problem. Als BürgermeisterIn bist du ein Teil der Gemeinschaft. Du kannst nicht nur leere Versprechungen geben. Du musst Ergebnisse vorweisen können. Städte sind auch flexibler und ergebnisorientierter als nationale Regierungen. BürgermeisterInnen sorgen für die Qualität des öffentlichen Raums. So ist zum Beispiel die Anzahl der Spielplätze in einem Bezirk sehr wichtig. Das klingt simpel, aber der öffentliche Raum ist ein Schlüsselelement dafür, wie die Menschen ihr Leben gestalten.

Sie sind einer von vier Bürgermeistern, die den Pakt der Freien Städte (englisch: Pact of free Cities) unterzeichneten. Damit positionierten Sie sich gemeinsam mit Budapest, Prag und Warschau als pro-europäisches und anti-autoritäres Städtebündnis. Mit welchen Absichten sind Sie dieser Allianz damals beigetreten und wie würden Sie deren Erfolge heute bewerten?

Der Pakt wurde als ein Bündnis der VisegradHauptstädte geschlossen, um ein Gegengewicht zu den antidemokratischen und illiberalen Kräften zu bilden. Wir sind durch unsere Werte verbunden. Wir wollen den Populismus bekämpfen, Transparenz fördern und bei gemeinsamen Themen wie der Klimakrise zusammenarbeiten. Natürlich gab es schon vorher Bündnisse zu verschiedenen Themen, aber dies ist vielleicht das erste Mal, dass diese Werte im Mittelpunkt stehen.

Der Pakt der Freien Städte wurde am 16. Dezember 2019 an der Central European University in Budapest unterzeichnet. Wenig später mussten die meisten Abteilungen der Universität aufgrund politischer Repressionen nach Österreich umziehen. Erst kürzlich wurde Viktor Orbáns nationalkonservative Fidesz-Partei wiedergewählt. Ist der von Orbán propagierte Illiberalismus wieder auf dem Vormarsch? Wie reagieren die BürgermeisterInnen des Paktes darauf und wie unterstützen Sie sich gegenseitig?

Der Illiberalismus ist auf dem Vormarsch, einige führende PolitikerInnen konnten zurückschlagen, aber die Schlacht ist noch lange nicht gewonnen. Der jüngste Sieg von Viktor Orbán ist ein Beweis dafür. Wir sehen, dass die illiberale Demokratie bestimmten Gruppen oder einzelnen BürgerInnen Vorteile verschafft. Wir sehen aber auch, dass die Situation in der Tschechischen Republik anders ist und dass in Polen bald Wahlen stattfinden werden. Warschaus Bürgermeister, Rafał Trzaskowski, ist eine große Hoffnung für uns alle. Auch in der Slowakei haben wir eine pro-europäische Regierung und ich freue mich darüber, wie sie die Dinge regelt, um der Ukraine zu helfen. Von dort, wo ich jetzt sitze, sind es nur sechs Autostunden bis zur ukrainischen Grenze. Dieser Krieg zeigt auch, dass Orbán im Unrecht ist. Seine Unterstützung für Russland bedeutet auch die Unterstützung eines Regimes, das unschuldige Menschen tötet. Wo sehen Sie die konkreten Vorteile in der grenzüberschreitenden Zusammenarbeit zwischen BürgermeisterInnen und Städten? Da gibt es zwei Ebenen: Erstens geht es darum, miteinander zu reden. Bratislava ist die kleinste Stadt unter den Gründungsmitgliedern. Daher waren wir sehr froh, als wir in den ersten Wochen des Ukraine-Krieges die Bürgermeister von Warschau und Prag um Know-how und Ratschläge bitten konnten. Ich bin nach Warschau geflogen und habe mich mit dem Bürgermeister darüber beraten, wie sich die Stadt darauf vorbereitet. Der Pakt bietet eine sehr konkrete und direkte Möglichkeit, Wissen auszutauschen. Die zweite Ebene ist die Bildung eines Bündnisses von BürgermeisterInnen mit den gleichen Werten, die auch bereit sind, auf europäischer Ebene für diese Werte zu kämpfen. Durch die Pandemieerfahrung ist die Position der Städte noch stärker als zuvor. Ich glaube, dass in vielen Ländern die Städte und ihre BürgermeisterInnen die Situation gut meisterten. Die Menschen nehmen die Städte als ihre Partner wahr. Deshalb ist es wichtig, die Kräfte zu bündeln und mit einer klaren Stimme zu sprechen.

© patri via Unsplash

In Medienberichten wurden die Gründungsmitglieder des Pakts auch als »liberale Inseln in einem illiberalen Ozean« dargestellt. Diese Metapher birgt jedoch die Gefahr, bereits bestehende Gräben zwischen der urbanen, oft liberaler eingestellten, Bevölkerung und konservativeren BürgerInnen in ländlichen Gebieten zu vertiefen.

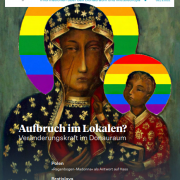

Ich verwende diese Metapher nie, und ich versuche auch nicht, diese Spaltung vorzunehmen. Ich bin mir über meine Werte im Klaren, aber als Bürgermeister setze ich mich für Dinge ein, die allen zugutekommen, etwa Spielplätze oder bessere öffentliche Verkehrsmittel. Das ist keine Frage von konservativen oder liberalen Werten. Wir haben Prides in Bratislava, aber wir unterstützen auch die OrganisatorInnen eines großen Treffens der christlichen Jugend. Ich arbeite mit konservativen und liberalen KollegInnen zusammen. Ich weiß, dass das schwierig sein kann, aber wir versuchen, die Menschen zu verbinden. Einige PolitikerInnen nutzen die Spaltung aus, weil sie wollen, dass sich die Menschen streiten, aber ich möchte lieber für eine gute Lebensqualität arbeiten.

Wenn Sie sich von der nationalen Regierung etwas wünschen könnten, das die Städte stärken würde, was wäre das?

Unser Verhältnis zur slowakischen Regierung ist nicht ideal. Auch nach COVID sieht man uns nicht als Partner. Wir brauchen klare Regeln und mehr Finanzmittel, denn im Vergleich zu anderen europäischen Städten sind wir sehr unterfinanziert.

Interview mit Daniela Apaydin und Matúš Vallo. Matúš Vallo ist ein slowakischer Politiker, Architekt, Stadtaktivist, Musiker und Bürgermeister von Bratislava. 2018 wurde er als unabhängiger Kandidat mit 36,5 Prozent der Stimmen an die Spitze der slowakischen Hauptstadt gewählt. 2021 zeichnete ihn der internationale Thinktank City Mayors mit dem World Mayor Future Award aus.