Energizing Cross-Border Cooperation in Central Europe

How can Central Europe cooperate most effectively on the energy transition? Michael Stellwag and Rebecca Thorne put the spotlight on CES7 (Austria, Croatia, Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia).

In the lead up to the European elections, the continent witnessed a backlash against green policies. The European Green Deal, which was introduced four years ago and outlines the continent’s path to climate neutrality by 2050, came under particular scrutiny. Integral to the Green Deal is the energy transition, including issues such as where the energy resources come from, how power is generated and who can access the final products.

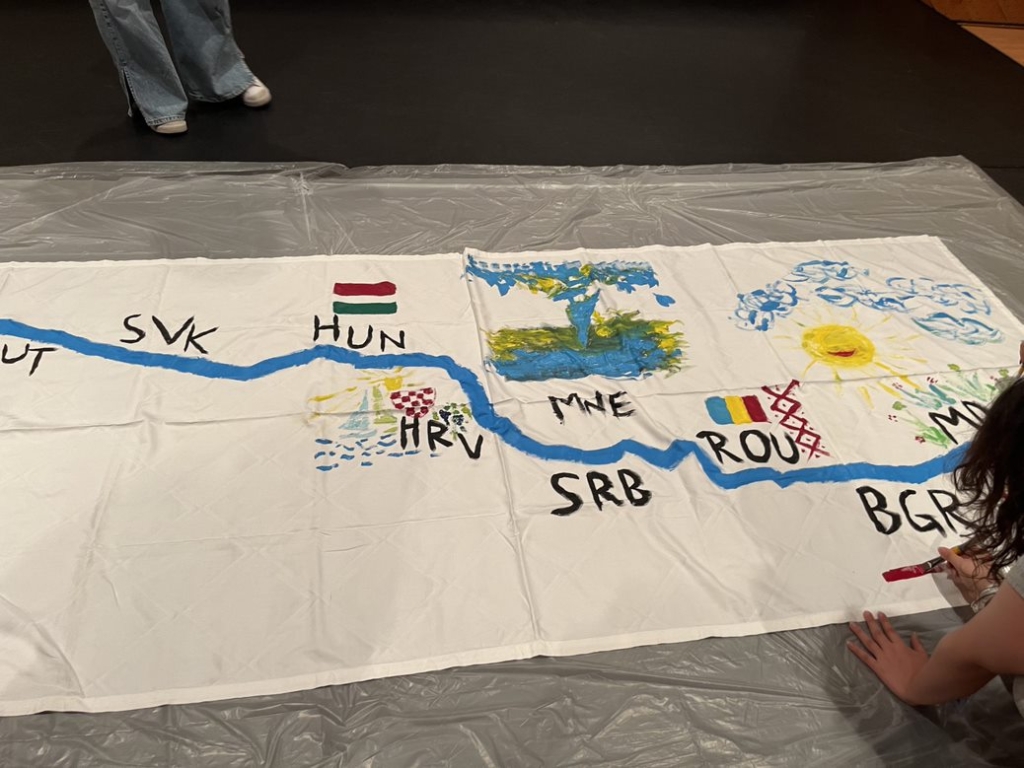

While the Greens did indeed lose influence in Germany, France and Belgium, they retained their seats in Austria and even gained their first seats in Croatia and Slovenia. Indeed, the seven Central European states of the EU – Austria, Croatia, Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia (CES7) – are faced with the tangible effects of climate change, geopolitical instability and economic challenges, which necessarily provokes discussion about the decarbonisation of the energy sectors in the region along with questions of security and affordability. Effective cross-border cooperation is key to solving this conundrum.

In the aftermath of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the knock-on effects on the prices and supply of energy across Europe, it may appear worthwhile pursuing the goal of self-sufficiency at national level to reduce dependency and the corresponding risk of vulnerability. However, not every country has the capacity to meet all their energy needs through domestic power generation. While some countries possess an abundance of natural energy resources such as wind, water and sun, others run the risk of continuing the detrimental resource exploitation of coal mining. Power generation from coal still dominates the energy landscape of countries with a history of mining, accounting for 44% of the total electricity generation in Czechia and 70% in Poland. Instead of maintaining or even exacerbating this trend, regional cooperation provides alternatives, some of which remain controversial, while others offer clear benefits.

Diversification and bridge technologies: different approaches

First of all, cooperation should not come at the cost of security. The region’s historical energy partnership with Russia has highlighted its vulnerability: reducing this dependence is crucial. The EU attempted to enforce immediate diversification by introducing an oil embargo against Russia in 2022. However, the Central European states without a sea border – Austria, Czechia, Hungary and Slovakia – pushed for an exemption, resulting in the continuation of imports of Russian oil via the Druzhba pipeline that runs through Ukraine.

Regarding the gas supply, even though the proportion of Russian pipeline gas in EU imports has fallen from over 40% in 2021 to currently 8% in the EU as a whole, the share in parts of Central Europe remains higher. Austria and Hungary are currently the most dependent on gas from Russia and have fought most intensively against possible EU sanctions. In Austria, the share of Russian gas in the total supply has not fallen significantly since the attack on Ukraine due to a non-transparent long-term supply contract that was extended in 2018 and to which, until recently, not even members of the government had access.

The response of these states to the energy supply crisis has been different. The four Visegrad states are primarily focusing on diversifying both their oil and gas suppliers in order to reduce their dependence on Russia without significantly reducing their consumption. Poland is using the Baltic Pipe as well as importing more from the USA, while increasing the capacity of its liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and pipeline infrastructure. Slovakia and Hungary are increasingly sourcing oil from Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, with security of supply being a priority – yet it is important to note that a certain amount of imports from these countries comes from Russia anyway. Czechia is also making efforts to diversify as well as focusing on energy efficiency measures.

In an example of minilateral cooperation, Austria has been investing in the LNG terminal on the Croatian island of Krk. This terminal has already existed for some time but is now being expanded far beyond the national requirements of Croatia in order serve as a regional hub. Poland has also been enlarging its LNG capabilities from 5 billion m³ a year via its Świnoujście terminal, aiming to double its capacity with the expansion and planned new construction in Gdańsk. The trend is clear: no reduction in gas, but the reduction of dependence on one single country. Yet a decrease in both would be possible with more intensive coordination and more coherent planning within the group – especially as investing in gas projects poses the danger of Central Europe tying itself further into a dependence on a resource that is ultimately a fossil fuel.

Nuclear power remains a contentious issue, with many convinced it is the way forward to reducing dependency on fossil fuels. In a further example of cross-border cooperation, Slovenia shares its nuclear power station with Croatia, which is in an earthquake zone and cannot build its own without compromising safety. Slovakia, Hungary and Czechia have also opted to invest in nuclear technologies: 59.7%, 44% and 36.6% of their respective electricity generation comes from nuclear. Hungary furthermore intends to increase this percentage with a new power plant that is to be built using Russian state funding. Poland currently has no domestic nuclear energy production but is developing plans to build its first nuclear power station.

However, others remain wary of a technology that has the potential to cause widespread harm. Austria is one of few outspoken opponents in Central Europe following the referendum of 1978 and subsequent law against generating nuclear power. Having set a goal to source 100% of its electricity from renewables by 2030, Austria moreover intends to show that the green transition is possible without nuclear energy.

Fast-growing markets

The renewable energy markets have been rapidly growing, especially the solar industry, with the demand for photovoltaic energy busting market expectations across Europe. There is also significant potential for energy generation from other renewable sources in Central Europe. Poland has begun to make use of the wind on its northern coast with its first offshore farm currently under construction, which is anticipated to generate 1.1GW. Nonetheless, there is still a lot of room for growth, with estimated potential for up to 33GW. Likewise, the Adriatic Sea offers considerable offshore wind power that is not being utilised. While it has been agreed that no wind farms will be built on Croatia’s islands, there is still an area of 29,000 km² that could be developed without encroaching on high-impact zones.

Furthermore, there are natural geothermal heat reservoirs across the region. Indeed, following the European Parliament’s recent call for an EU geothermal energy strategy, the European Committee of the Regions released an Opinion on the “great potential” of geothermal for both cities and regions. To give three examples from the region: in Poland, geothermal reservoirs have been found in around 50% of the country’s area, particularly in central and northwestern Poland. Hungary has already quadrupled its use of geothermal energy since 2010 and is now planning to double its use again by 2030, while Slovenia has been developing a pilot geothermal project that only requires one dry well for operation.

Prioritise the grid

With such promising potential of renewables, both large- and small-scale, what is preventing an exponential growth of the clean energy sector? The supply chain is currently not the limiting factor in terms of what is possible. While the manufacturing of solar panels is at present dominated by China, the EU has established initiatives such as the Net Zero Industry Act and the European Solar Charter, which aim to support solar manufacturing in Europe.

Instead, with a rapid expansion of the renewable energy sector, the grid is the main bottleneck. Energy systems are largely centralised through national grids, which currently do not have the capacity to integrate the rapidly expanding renewable sector. Sectors that were predominantly running on fossil fuels are now being converted to electricity. To further complicate the problem, the grid in Poland, for example, is concentrated on regions in the south of the country that produced energy from coal, whereas the up-and-coming renewable sector is focused on the north. Moreover, the grid does not offer sufficient capacity for large projects at sea.

Cooperation among the countries of Central Europe would allow a pooling of renewable resources, which is indispensable given the fluctuating nature of supply and demand inherent to renewable energy. Within this partnership, a priority must be the full synchronisation of the grid across the region as well as the expansion of cross-border grid interconnectors. In particular, the triangle between Austria, Hungary and Slovenia has been identified as critical.

Huge potential

The European Green Deal promises long-term potential for growth, but currently the transition requires significant financial investment, challenges the economies and could threaten established industries in this underperforming region. Among some governments and sections of the population in the Central European countries there are narratives that they are second-class countries within the EU. Many regulations are seen as originating from Western European countries and Brussels, which member states then have to implement regardless of economic feasibility, resulting in a sluggish implementation of individual EGD regulations. Nonetheless, renewable energy sources, even in the year of installation, are cheaper than fossil fuels. In 2022, the global average cost of solar energy was 29% lower than the cheapest fossil fuel option, while the cost of onshore wind energy was 50% lower. An integrated grid would also boost price competitiveness as cheaper, cleaner electricity from neighbouring countries in the region becomes available to consumers.

Central Europe has significant potential for a green energy transition, as well as for a more dynamic economy and policymaking than is often assumed. Cooperation is essential to accelerate progress – whether a pooling of financial, knowledge or human resources. With the rapid growth of renewables and increasing electrification of the energy sectors, the expansion and improved international interconnectivity of the grid must be a priority not only for the EU, but also on regional level.

Rebecca Thorne is a research associate at the Institute for the Danube Region and Central Europe (IDM) in Vienna. Her research focus is climate, energy and the environment in Central Europe and the EU candidate countries.

Michael Stellwag is a research associate at the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Vienna. Having studied political science in Vienna and Tallinn, he now specialises in politics in Central and Eastern Europe and in EU foreign, security and defence policy. Professional projects have taken him to numerous countries in the region.

Both authors attended the expert workshop “Central Europe Plus – Bridge technologies with regard to a sustainable energy supply” organized by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Zagreb. The workshop series has existed since 2021 and focuses on the role of Central European States for the future of the EU. It aims to bring together decision-makers and researchers from the countries concerned and to present positions and demands from these countries in Brussels. In 2024, the project has been developed further to include other regions as well, hence the workshop title Central Europe Plus.